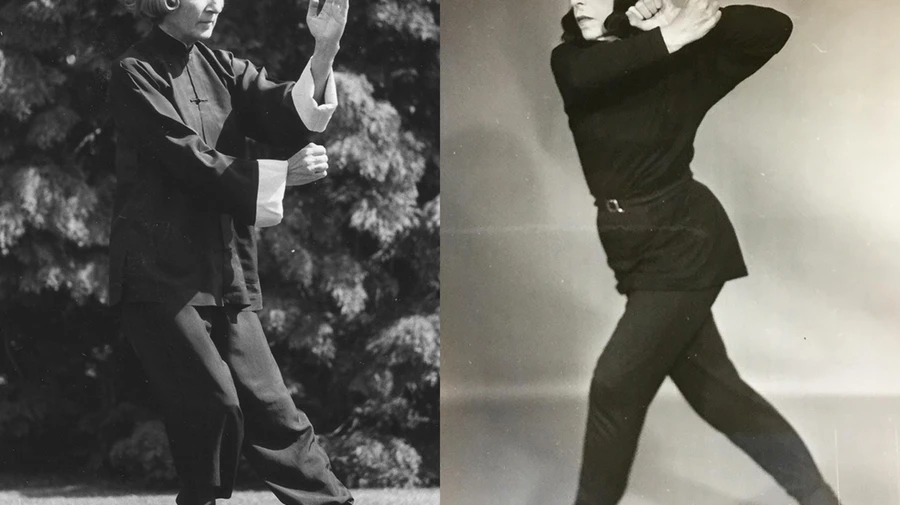

The forgotten pioneers of Tai Chi, Sophia Delza and Gerda Geddes, were fascinating women who first introduced the art to the western world in the 50’s! They were dancers! Furthermore, Geddes was developing an embodied approach to mental health combining dance and psychotherapy, when she discovered Tai Chi.

In his article “THE FORGOTTEN (FEMALE) PIONEERS OF TAI CHI IN THE WEST”, journalist Charles Russo tells their stories:

As dancers, both Delza and Geddes had initially embraced Tai Chi as an alternative and holistic approach to dance and movement. In time, Delza would continue to promote the art from a health perspective, while Geddes would increasingly embrace its’ spiritual aspects. Both were aware that they were practicing what was essentially a martial art, although fighting was never their goal.

Delza was American. She trained in modern dance and had a career that spanned stage and film. Following her husband to Shanghai in 1948, she broke ground as the first American dancer to perform and lecture in Chinese theaters and dance schools.

Geddes was born in Norway. She also trained in modern dance at a young age, before studying psychotherapy at the University of Oslo. By the time she followed her husband to Shanghai in 1949, she was developing an idea to merge her studies in dance and psychotherapy to create a physically-oriented approach to mental therapy. As she watched an elderly man perform Tai Chi at dawn, Geddes realized the Chinese had been cultivating one for centuries.

Delza was also learning Tai Chi in Shanghai during the same year. Few westerners at the time had any exposure to the practice, but both quickly found value in what they were witnessing. Geddes and Delza trained separately under renowned masters before bringing the art back to their home countries. In a curious mirror image of one another, the two played pioneering, though widely forgotten roles, in the early martial arts culture of the West, spreading Tai Chi far beyond China, and launching it towards its current popularity

This modern appeal is fascinating to consider as Delza and Geddes both envisioned Tai Chi’s relevance and potential health benefits more than a half century ago.

The notion of western women learning Chinese martial arts was unprecedented at the time.”These Chinese men had very great trouble with me because women didn’t do tai chi in those days,” Geddes would later explain. “Most women still had bound feet.”

Although they were confronted by a Chinese martial arts code excluding foreigners and women, the language barrier, and the tumultuous circumstances in communist China, Geddes and Delza managed to study with established Chinese masters. Delza studied Wu style under Mah Yueh-ling in Shanghai, and then returned to promote the art in New York City. Conversely, Geddes learned Yang style under Choy Hak Peng in Hong Kong before returning to teach in England. These were relationships that defied the social boundaries of their era. In the same time and environment a teenage Bruce Lee was banned from Ip Man’s Wing Chun school on account of his quarter European ancestry.

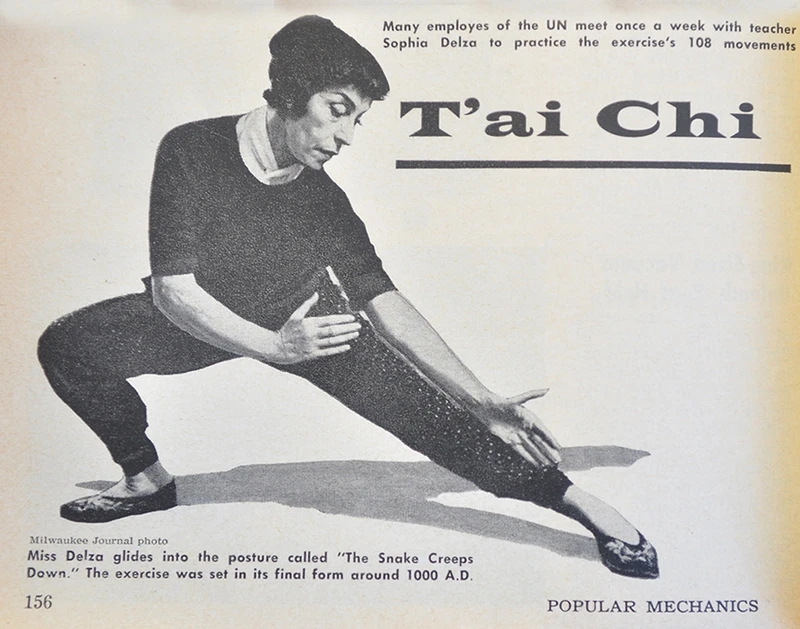

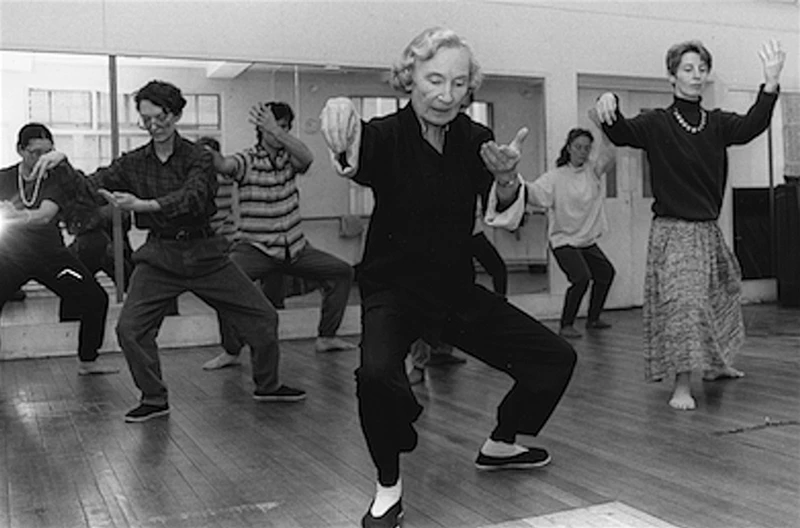

Geddes’ efforts to promote Tai Chi were initially met with confusion and disinterest, while Delza quickly found traction by showcasing the art in high profile settings around New York City. In 1954 she staged a public demonstration at the Museum of Modern Art. The interest that was generated from these demonstrations would led to her conducting regular classes at Carnegie Hall and the United Nations. Geddes’ efforts finally gained momentum at the London Contemporary School of Dance, which eventually incorporated her classes into their freshmen curriculum. Within a year of each other, both women gave what were presumably the first televised Tai Chi demonstrations in their respective countries.

In 1961, Delza authored what is possibly the first English language book ever written on the Chinese martial arts: T’ai-Chi Ch’uan: Body and Mind in Harmony. As she explained in the opening chapter, her intentions were “to bring to the attention of Western people this ancient masterpiece of health exercise…which…is supremely suitable in these modern times.” Delza and Geddes had a wellbeing vision for this ancient art in the modern world. However, by the early 70s, the kung fu craze was in full swing, and the mind and body health culture envisioned by Geddes and Delza took a quiet back seat. Action movies and esoteric fighting techniques emphasized the fighting component of Asian martial arts in the west. The contributions of Delza and Geddes didn’t fit the prevailing narrative of dynamic fighting skills. The two women were largely excluded from coverage despite almost singlehandedly introducing Tai Chi to their respective continents as well as conducting careers that spanned four decades and thousands of students.

With hindsight, despite criticism and obscurity Delza and Geddes seem to have prevailed in their vision. They sowed the seeds for Tai Chi in the west. Their students (and their student’s students) now teach in countries around the world. Since their passing—Delza in 1996 and Geddes in 2006—Tai Chi’s popularity has spread around the world. Its health benefits are increasingly backed by clinical studies. Thankfully, eventually Delza and Geddes were quietly successful in their vision,

Charles Russo is a journalist in San Francisco. He is the author of Striking Distance: Bruce Lee and the Dawn of Martial Arts in America, which chronicles the pioneering martial arts scene in the San Francisco Bay Area during the early 1960s.

1 thought on “Forgotten pioneers of Tai Chi in the West”

Comments are closed.